Spotlight: Zeinabu irene Davis

- Invisible Women

- Feb 8, 2022

- 10 min read

“Once I started making films I just realized I had to keep making films.

It’s like breathing to me, which means I’m not happy unless I’m doing some kind of filmmaking. I don’t have to be on set or in production but if I’m not thinking about making work, or finishing work in the editing room, then there’s a part of me that’s just dead”

A young woman is in her apartment, waiting for something. Fresh flowers sit on her dresser, incense burns. As she goes about daily rituals, cleaning the floor, making her bed and taking a bath, disembodied voices ebb and flow. We don’t know where these voices come from – they could be pure imagination, snippets from remembered conversations, or the whispers of ghosts – but they are comforting. “You’re doing alright and you’re gonna get better,” they repeat reassuringly, “progress is being made.”

These images come from Cycles (1989), an early short from Zeinabu irene Davis. Cycles is a tiny wonder, a miniature epic contained within the confines of one apartment and one woman’s mind. Across the course of 19-minutes, Davis invites us inside the home, the thoughts and the dreams of her protagonist, introducing us to her friends, her ancestors, and her desires. It’s a beguiling, singular piece of work, the kind of film you want to urge on people, to press into their open palms.

Cycles announces Davis as a major talent. Who else, after all, could have made such a beguiling, memorable film from a scenario so simple (and static) as a woman waiting for her period?

Zeinabu irene Davis was born in 1961 in Philadelphia. As a young woman she studied Law at Brown University, but later switched her focus to filmmaking. This conversion was partly triggered by a time Davis spent in Kenya as an undergraduate studying under the famous dissident writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. It was while working on a production of one of Thiong’o’s plays, an experimental piece exploring British colonialism and the Mau Mau uprising, that Davis was first struck by the power of art to confront history. Although Nairobi was full of white European filmmakers, Davis noticed that they seemed more preoccupied with the areas wildlife and landscape than the experience of Kenyan people. Surrounded by people who were almost entirely unrepresented in film, Davis found her calling. She returned to the US galvanised - she would dedicate her career to telling their stories.

Throughout her twenties Davis continued her studies, eventually arriving at the Film and Video Masters programme at UCLA. Here she found herself in the creative hub for a kind of golden period for Black independent filmmaking. During the 1970s and 80s, the likes of Julie Dash, Alile Sharon Larkin, Barbara McCullough, Charles Burnett and Haile Gerima had emerged from their studies determined to forge their own cinematic aesthetic. They formed a loose collective, working together to make micro-budget experimental films which drew inspiration from anti-colonialist and black power movements. These artists worked on each other’s projects and taught themselves to do everything – writing, producing, directing, sound, editing and mixing independently. “We weren’t making films to be paid, or to satisfy someone else’s needs,” said Dash to the Guardian in 2015. “We were making films because they were an expression of ourselves: what we were challenged by, what we wanted to change or redefine, or just dive into and explore.”

As a teenager in Philadelphia, Davis had encountered early films of the LA Rebellion – works such as Melvonna Ballenger’s Rain (1978) and Ben Caldwell’s I & I: An African Allegory (1979). The prominent presence of women within the movement must have been inspiring to Davis. She was a generation younger than the LA Rebellion’s main players, but would have been surrounded by their influence. By the end of the decade, Davis had graduated with an MFA and a couple of calling card shorts.

One of those shorts helped to establish Davis immediately as a name to watch. Revisiting Cycles today, it’s easy to see why. Still so fresh, so confident, it’s a film of wonderful restraint with a sense of scale that belies its simple premise.Those languorous early interior scenes are blown open in the final third by a glorious dream-sequence. As our heroine swaggers through the streets with friends, running and playing jokes, dancing in the road, we are reminded of how rarely we see images of joyful, young liberated Black womanhood through the eyes of young, Black female filmmakers.

Another key strength of the film is its distinctive aesthetic. Shot in inky black and white, Cycles combines still images, animation and 16mm, a mash-up of styles that adds to a sense of magical otherness, the everyday made strange and new. The soundtrack is a collage of music – Miriam Makeba singing, Clora Bryant trumpet, Haitian chants – and snippets of layered voiceover, which combine to form lapping waves of sound. Glimpses of Afro-Caribbean traditions connect this vision of contemporary urban America to a deeper diasporic history.

Cycles ends with a sigh of relief as that much anticipated period finally arrives. A clot of blood on the sheets is depicted with calm matter-of-factness, an image which pre-figures by three decades a similar, much-admired moment in Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You (2021). Davis presents this with soothing understatement - the blood arrives, the cycle continues, life goes on.

Cycles put Davis on the map, earning her plaudits from the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame and the National Black Programming Consortium. It was an auspicious start to a career that seemed to be starting at just the right moment.The early 1990s were an exciting time to be a young Black filmmaker in the US. Building on the trails blazed by the LA Rebellion, Black independent filmmaking seemed finally to be having a mainstream moment.The success of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and Do The Right Thing (1989), had announced a public and critical appetite for black filmmaking, and although Lee would remain an outlier in terms of success and longevity, he had a decent number of male and female peers.

In 1991, Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust became the first narrative feature directed by an African American woman to receive a theatrical release in the US. Although the film had its antecedents – Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground (1982) had received limited screenings on the festival circuit a decade earlier – this was undeniably a watershed. Daughters of the Dust was followed by a steady flow of excellent films helmed by Black women, such as Leslie Harris’s Just Another Girl on the I.R.T. (1992), Darnell Martin’s I Like it Like That (1994), Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) and Kasi Lemmons’s Eve’s Bayou (1997).

It’s important not to gloss over the struggle here - Black female filmmakers still enjoyed considerably less attention from critics and distributors than their male peers, and Dash initially had to drum up her own audiences, driving around with the reel in the back of her car - but nonetheless it was a moment of hope. It was within this optimistic context that Davis continued to make films, gathering the momentum to make her first feature.

Across the 1990s, Davis continued to make remarkable short and mid-length work, which explored abiding themes such as gender, the body and African diaspora. A Powerful Thang (1991), which centres on a single mother in Ohio, as she negotiates her sexuality in the aftermath of a period of celibacy, built on Cycles’s use of Afro-Haitian dance and animation techniques. The magical realist Mother of the River (1995) demonstrated Davis’s interest in period settings and Black history, telling a story from the perspective of a young enslaved girl in the 1850s. For her first narrative feature, Davis would build on the foundations laid by these shorts, embracing the opportunity to bring her aesthetic and thematic concerns to a larger canvas.

Compensation (1999) charts two parallel love stories taking place in Chicago at opposite ends of the twentieth century. Both romances occur between a deaf woman and a hearing man, played by the same actor in each story. In the first strand, the fiercely intelligent Malindy (Michelle A. Banks) who has been expelled from her specialist deaf school because of new segregation laws, falls in love with poor, illiterate travelling minstrel Arthur (John Earl Jenks). In the second, young librarian Nico (Jenks again) courts headstrong graphic designer Malaika (Banks), learning ASL in an attempt to persuade her that relationships between deaf and hearing people can work.

The two interweaving narratives also lean into heightened emotions and dramatic plot twists. Both are Romeo & Juliet stories about (possibly) doomed love across social divides, which throw endless hurdles at our poor struggling lovers – pressure from friends and family, money issues, class differences and even deadly illnesses. In early twentieth century Chicago, it is tuberculosis that threatens to part the characters, an illness that has historically been closely associated with artists and sex workers – so much so that in the 19th century it was nicknamed “the romantic disease.” In the 1990s strand, the existential threat comes from HIV/AIDS, another illness that was closely associated with outsiders that exacted a particularly potent toll in the art world. Watching in a pandemic, it’s impossible to miss that both are contagious diseases that have historically provoked considerable social stigma. When Arthur appears to deliver a message to Malindy dressed in protective clothing it inevitably brings to mind both the terror of the early days of the HIV/AIDs crisis, and the recent normalisation of mask wearing during our current ongoing pandemic.

Shot in black and white and constructed around intertitles, Compensation pays homage to early cinema. In one scene, Arthur takes Malindy on a date to the cinema, and Davis shows us a gentle parody of silent cinema with its hacky acting and melodramatic stories. Yet this reference to early film is more than a tip of the hat. By mimicking the form and structure of a silent movie, Davis bridges the gap between those who hear and those who don’t, presenting a film that can be enjoyed on almost equal terms by both hearing and deaf audiences. She also gestures towards a lost history of African American filmmaking. The film that Arthur and Malindy watch is based on a real lost silent from 1915, The Railway Porter, which was made by an all Black company for Black audiences. Davis read a description of the film in the archives of a Chicago newspaper, and chose to reconstruct it for her homage, reminding us that Black filmmakers (like female filmmakers) have been active in cinema since the birth of the medium.

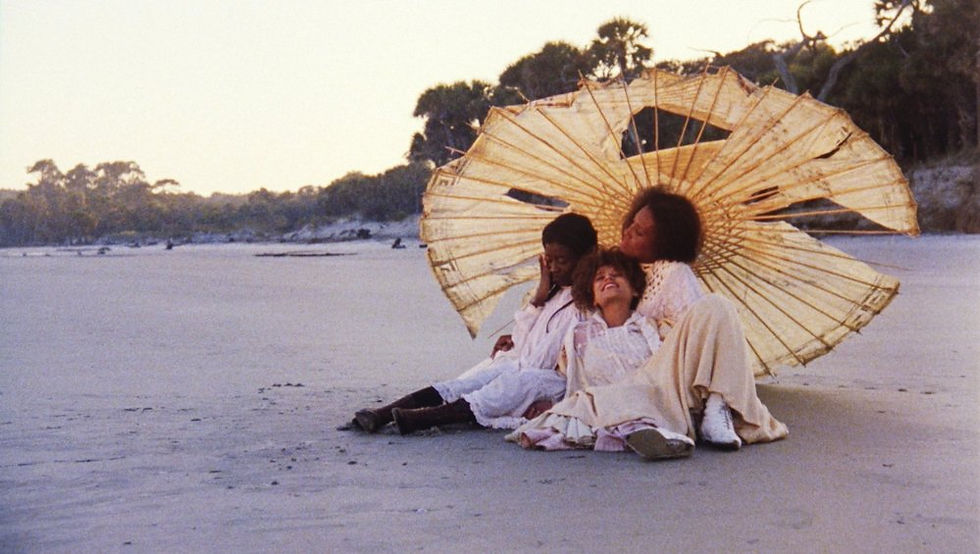

Davis makes similar leaps of creative imagination throughout Compensation. The film is full of real archive images, taken from turn of the century America, but these genuine artefacts are mixed in with apparently re-constructed footage and images. Like many of the best creative ideas, this imagined archive was an invention born of necessity – on an $100,000 budget, Davis did not have enough money to recreate period locations. This technique has the effect of creating a blur between drama and archive, making it difficult to discern what is “real” documentation and what is reconstructed “fiction.” In this sense, it connects directly with films such as Barbara Hammer’s The Female Closet (1998) and Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1995) which also attempt to fill gaps through experimental techniques and artistic reconstruction. Elsewhere, Davis seems to reference her artistic ancestors. Scenes of Malindy lying under a parasol on the white sands of a beach in period dress are reminiscent of images in Daughters of the Dust. Sequences in which Malaika debates issues of deaf civil rights with her friends bring to mind the passionate talky energy and intellectual heroine of Losing Ground.

Compensation also reflects powerfully on lasting divisions and segregation in America. In the first story, Malindy is furious in the face of segregation laws which limit her ability to continue her education. In the second story, we see that civil rights battle reflected elsewhere, in the battle of the ASL-speaking deaf community to achieve recognition as a valid community in their own right and of the struggle of those living with HIV to participate in society. In an early scene, a friend tells Malindy that her mother thinks it’s a shame that despite her beauty and intelligence, she will be held back because she is “deaf and dumb.” Malindy's face freezes into a look of contempt. “I am not dumb” she writes in reply.

Compensation premiered at Sundance in 2000, where it was warmly received by critics. But despite this reception it never received wider theatrical distribution. Aside from festival outings at Toronto and Atlanta, and a few one-off screenings elsewhere, it was never released in cinemas. It was picked up by the ever brilliant Women Make Movies, who currently license screenings of most of Davis’s work, and this at least means that it is possible to track down rights and material to screen. Yet, the lack of mainstream distribution interest in the film means that it has never truly reached a wide audience outside of cinephilic circles. Given the context in which it was made – a moment of real optimism for independent African American filmmakers – this feels like a missed opportunity.

There are however signs of hope. In recent years, as the industry grapples once again with its exclusionary history, there has been a resurgence of interest in LA Rebellion filmmakers. The 25th anniversary of Daughters of the Dust in 2016 brought the film back into cinemas to the delight of both audiences and critics. Meanwhile, 2022 has already seen at least two screenings of Davis’s work in Europe – A Powerful Thang in London and Cycles/Compensation in Berlin. It was the latter screening that allowed us to fall in love with Davis for the first time.

Davis has not made a narrative feature since Compensation, although she has continued to make shorts and documentaries, and is currently Professor of Communication at the University of California in San Diego. Davis’s most recent film Spirits of Rebellion: Black Cinema at UCLA, (2016) is a documentary about the LA Rebellion filmmakers, which argues that their influence extends way beyond the 1990s into contemporary indie filmmaking. Fittingly, Spirits of Rebellion takes Davis right back to where her love of cinema began, connecting the veteran filmmaker with the teenage girl in Philly whose horizons were expanded by Ben Caldwell and Melvonna Ballenger. The circle closes, the cycle continues.

Watch Zeinabu irene Davis’s films over at Women Make Movies.

If you’re interested in the history of Black independent filmmaking in the US, check out our pieces on Fronza Woods and Kathleen Collins.

Selected Filmography

Trumpetistically Clora Bryant (1989)

Cycles (1989)

A Powerful Thang (1991)

Mother of the River (1996)

Compensation (1999)

Spirits of Rebellion (2016)

Reading

Quotes and biographical information taken from Glenn Heath Jr’s newsletter, “Loving so Deeply: An interview with Zeinabu irene Davis”, 2020.

Sundance Institute, “Compensation”.

Emerson Goo, Screen Slate, “Compensation”, 2021.

Grace Barber-Plentie, LSFF, “A Powerful Thang”, 2022.

Julia Thelsanthal, Vogue, “Director Julie Dash on Daughters of the Dust, Beyoncé, and Why We Need Film Now More Than Ever,” 2016.

Ashley Clark, The Guardian, “The LA rebellion: when black film-makers took on the world – and won,” 2015.

Women Make Movies, “Compensation.”

Sangeeta Singh-Kurtz, The Cut, “On I May Destroy You's Beautiful Blood Clot”, 2020.

Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, Women Film Directors: An International Bio-critical Dictionary, 1995.

Let all your fantasies flame out effectively in Delhi with our alcoves. Beautiful, charming, and sensual; the Call Girls in Delhi have been handpicked for you. Let us show you how to fulfill your desires through our escorts' Delhi services. Call our Delhi escorts agency for a heavenly pleasure bliss.

Kaiser OTC benefits provide members with discounts on over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and health essentials, promoting better health management and cost-effective wellness solutions.

Obituaries near me help you find recent death notices, providing information about funeral services, memorials, and tributes for loved ones in your area.

is traveluro legit? Many users have had mixed experiences with the platform, so it's important to read reviews and verify deals before booking.